La Confidence and Seeing is Believing

A Compost Heap breakdown on wtf is going on in this picture and why female friendship is perhaps the greatest, most underrated, artistic subject matter.

Welcome to Flotsam's compost heap, a mulch of art that has provided me with inspirational fodder. Neil Gaiman talks about the importance of having a creative compost heap: what you read, see, hear, encounter, and experience all gets mulched together to rot down and mingle. Somewhere down the line, it will act as fertiliser and nutrients from which your own stories and art will flourish.

Ever have that experience of looking at a work of art and thinking it’s about one thing and then reading the description and going, hmm, really? Are we looking at the same thing?

This happened to me with La Confidence recently.*

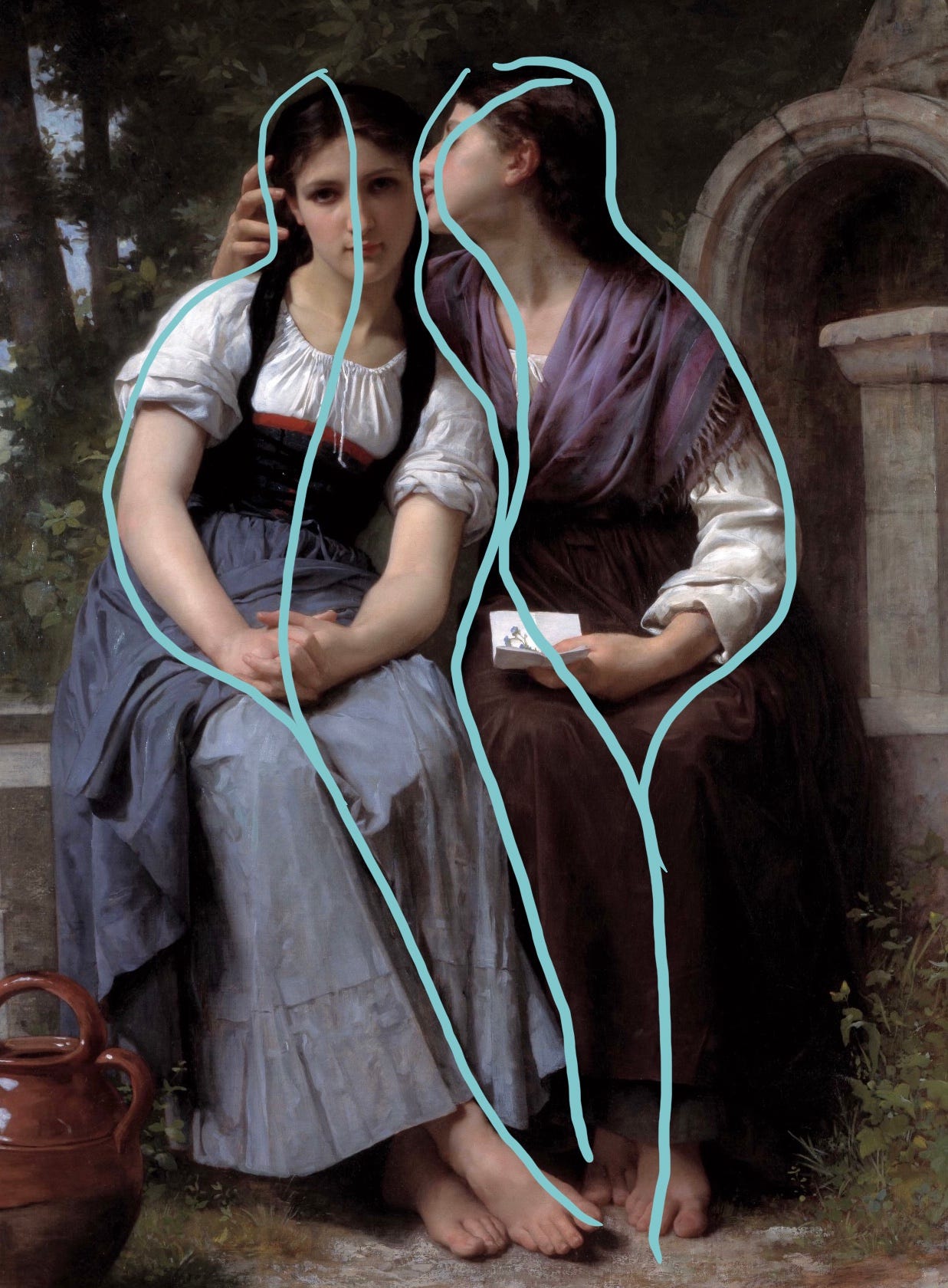

When I saw this painting, my response was, first, visceral; second, intrigue; third, excitement. The intimacy of the two… women? Girls? Creatures that epitomise the post-puberty, pre-adulthood limbo that is adolescence in all its shit-show glory. The way their bodies almost fuse together, twisting in and away from each other, is a masterclass in the convergence of composition and narrative. The chin-tilted profile of the girl on the right with her soft hand caught between a caress and a grab (and whilst we're here, is she whispering something in her companion’s ear or about to brush her lips against her cheek?). And the pure insolence, knowingness, challenge, in the expression of the girl on the left, half her face illuminated and the other half caught in a shadow that almost swallows her eye. What's the relationship between them? Because it doesn't take much to realise that their hair is the same shade of chestnut; they share long aquiline noses, strong chins, and large ears. It's not a stretch to imagine that if both girls were head-on, you would be looking at the same face…

And then I read the description, and my brain was rattled—because what I was reading about the painting didn’t quite map onto what I was seeing.

The description told me that the title La Confidence translates to The Secret. Makes sense. But the description also told me that the title ‘most likely refers to the letter one of the young girls holds.’ (But, don’t we whisper secrets into ears?). Then it listed the themes: privacy, purity, and trust—conveyed through the iconography: the crossed legs represent ‘feminine modesty,’ as does the pitcher in the foreground. The cross behind them signals ‘moral cleanliness.’

I had to do some digging to determine why a pitcher is synonymous with feminine modesty. There’s a string of paintings titled ‘The Broken Pitcher’ or similar, which depict girls who have lost their virginity and, therefore, their modesty, reputations, and basically any social currency they possessed as females—starting with Jean-Baptiste Greuze in the late eighteenth century.

The paintings of this thematic sub-genre are all disturbing in their own ways, but two damning properties they share are that, firstly, they show girls, not women. And not, I would argue, even adolescents; these kids look like they are barely skimming puberty. Secondly, the paintings are intended to condemn these girls and offer up a warning about being a slut and becoming spoiled goods. In a strange twist (or is it?), Gardner’s husband, William-Adolphe Bouguereau painted one of the most famous examples of this trope in 1891. (Yes, it was the Victorian era, but the fact that a child being raped is used as a moral warning to women is still horrifying—although unfortunately not surprising).

I would like to think that Gardner is critiquing this theme in some way by including this symbol in a painting that doesn’t seem to quite be about female innocence, and also doesn’t really look like a warning to girls about jeopardising their modesty.

I’m not saying La Confidence doesn’t toy with the themes of modesty and morality or privacy, purity, and trust—it almost certainly does. But surely this picture is about complicating them? Surely the inclusion of such a prominent pitcher at the foot of two such interesting figures is more of a textured, nuanced discussion of purity and female sexuality. The painting seems to say one thing on the surface in its symbols—but it's communicating something different.

It seems to be more about intimacy, desire, and choice than privacy, purity, and trust.

To return to the title, The Secret is a fitting name—something is going on here that the viewer isn’t privy to. Secrets come in many forms, but they are concealed, partially known things, often abundant with risk or horror or deliciousness. To say the name of the painting is derived from the letter in her lap is to eliminate the physical intimacy of the two girls.

The sensuality in how the secret is being shared—an unknown passed from one girl to the other—coupled with how the girls are staged hints at the complexities at the heart of this image. The strong diagonal slope of the whispering girl’s nose pulls our attention to her companion’s eyes, which lock with the viewer’s. By acknowledging us, she is inviting us into their duo—and at the same time, excluding us, reminding us that we can’t know what’s being shared.

And if we could only know what was being whispered, would that settle the debate about whether the subject of the painting leans more towards modesty or transgression? Because this small curve through the centre line created by the bridge of one girl's nose to her friend's face is just the start of a zingy synergy that rips through this canvas. Their entire body language is a windy, twisty, deeply satisfying journey to some richer subtext.

Lines of Beauty or Something of the Sort

Line of beauty is a term and a theory in art or aesthetics used to describe an S-shaped curved line (a serpentine line) appearing within an object, as the boundary line of an object, or as a virtual boundary line formed by the composition of several objects. [...] According to this theory, S-shaped curved lines signify liveliness and activity and excite the attention of the viewer as contrasted with straight lines, parallel lines, or right-angled intersecting lines, which signify stasis, death, or inanimate objects.

A quote I pulled from wikipedia that has no citations but sounds right to me.

When considering the figures, body language is a bit of an understatement—it’s not just what their bodies are communicating but how they’re shaping, forming, and interlocking.

Quite remarkably, hundreds of philosophical tomes and treaties have been written trying to qualify and quantify what makes something beautiful. Seeing as beauty and taste are subjective—individually and culturally—and its metrics are constantly changing, this is a potentially redundant task… and yet, some very lovely and interesting ideas have emerged from this pursuit (as well as some toxic ones).

One such mainstay is ‘the line of beauty’, or William Hogarth’s idea that serpentine lines, especially when embedded in the human form, appeal most to the viewer. Hogarth liked the very literal ‘S’ shape, but serpentine lines (like serpents themselves) are just winding curved lines. Also, like a serpent, they are sinuous and dynamic, conveying a certain kind of energy.

I actually think ‘line of beauty’ is a misnomer, I think they are more satisfying and interesting than beautiful, but I also think the ‘line of beauty’ is a charming name (particularly if you reinterpret it, such as Alan Hollinghurt did to mean anything from dogging on Hampstead Heath to lines of cocaine).

Let me talk you through some lines of beauty I drew earlier…**

Or just enjoy the view:

The curve, which runs between the girls, pulls focus to the midline of the entire canvas. This line does more than snake between them; it occupies a shadowed space between their bodies, blurring where one girl ends and the other begins.

Naturally, we are drawn to the girl on the left because she is looking out at us. Her body betrays an interesting conflict; whilst her head tilts gently towards her companion, her torso bends away, and then her legs curve sharply back into the other girl, ending at the kick of her toe. Whereas the twist in her body hints at uncertainty or conflict, her friend is fully invested: not only is she oblivious to or ignoring the viewer, she is fixed on—and to—her friend as her midline almost fuses with the shadowed centreline.

The curves that case the outside of the girl’s bodies running from their heads down their arms, are a surprise treat: their outer boundaries are almost the exact same shape. This mirroring is not only genius because it is compositionally satisfying; it reveals a lot about these two girls—they are a pair, a unit, a coupling (or two versions of the same person if you recall their shared features). Within their forms, they are independent and display conflict and investment, but they exist as a duo.

So what does this all mean?

That La Confidence is about transgressing modesty and sexual female intimacy is how the painting was reinterpreted by artist and filmmaker James Herbert for R.E.M’s music video to Low. It’s a lovely video, and I think Herbert and I have similar readings on the painting in many ways, but we also diverge sharply: I don’t think these girls are lovers. I think they are best friends.

For the last year and a half (in the name of research), I have embarked on an almost anthropological study of best friends. Specifically, female adolescent best friends. They were probably your first love. They were almost certainly your worst, and most cherished and revered, person. Their opinion mattered more than anybody else’s. One cruel word or look from them was devastating. As you grew together and figured yourselves out, including sexually, there may have been something erotic or romantic. I don’t mean literally or in abundance, just a faint and fleeting charge.

So despite what the description says, I do not think the painting is about the letter from a (presumably) male suiter and female virtue in a male world. Or, it’s about this in part, but that is not the interesting bit. I think if you actually look at the painting, it’s all about the girls.

And when I look at these two girls, secrets in hand, drawn to, but conflicted, inviting you in but signalling you will never be part of their duo, two halves of a whole, I see the very best kind of friendship.

* I have never seen this painting in person, only digitally. Seeing art online is different from in person; I often get more out of the digital experience (… another post for another time). Come for me, art snobs.

** Did I quite literally have to sign up to YouTube to do this? Yes. Was this the first time I have ever added voice-over to a video? Yes. Did the entire process make me question everything about myself, life, and the universe? Yes. Am I also a bit proud of myself for facing this ridiculous fear? Also, yes.

Eye icon used by Duygu Ozkan