Why Have There Been No Great Women Subjects (painted by women)?

A post-script to my thoughts on La Confidence

Women painted (or sculpted, etched, etc.) by women are often fascinating. As I said about La Confidence, you can sense how differently women relate to the women they are depicting than male artists rendering female subjects do.

But there’s something in particular about the artworks of women by women that occurred before the 1970s (only fifty years ago!). Or specifically, before Linda Nochlin blew the art world’s mind with her essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? In the most sweeping terms, art post-Nochlin’s seminal essay often consciously challenges the male gaze, and the works are often analysed in that light. But I would also say, for many hundreds of years pre-Nochlin’s battle cry, women artists were subverting the male gaze in their depictions of women. (However, as Nochlin points out, the art world struggled to take women artists seriously. And what was worse than a woman painting female experiences…).

So, in short, there’s something about the way women paint women.

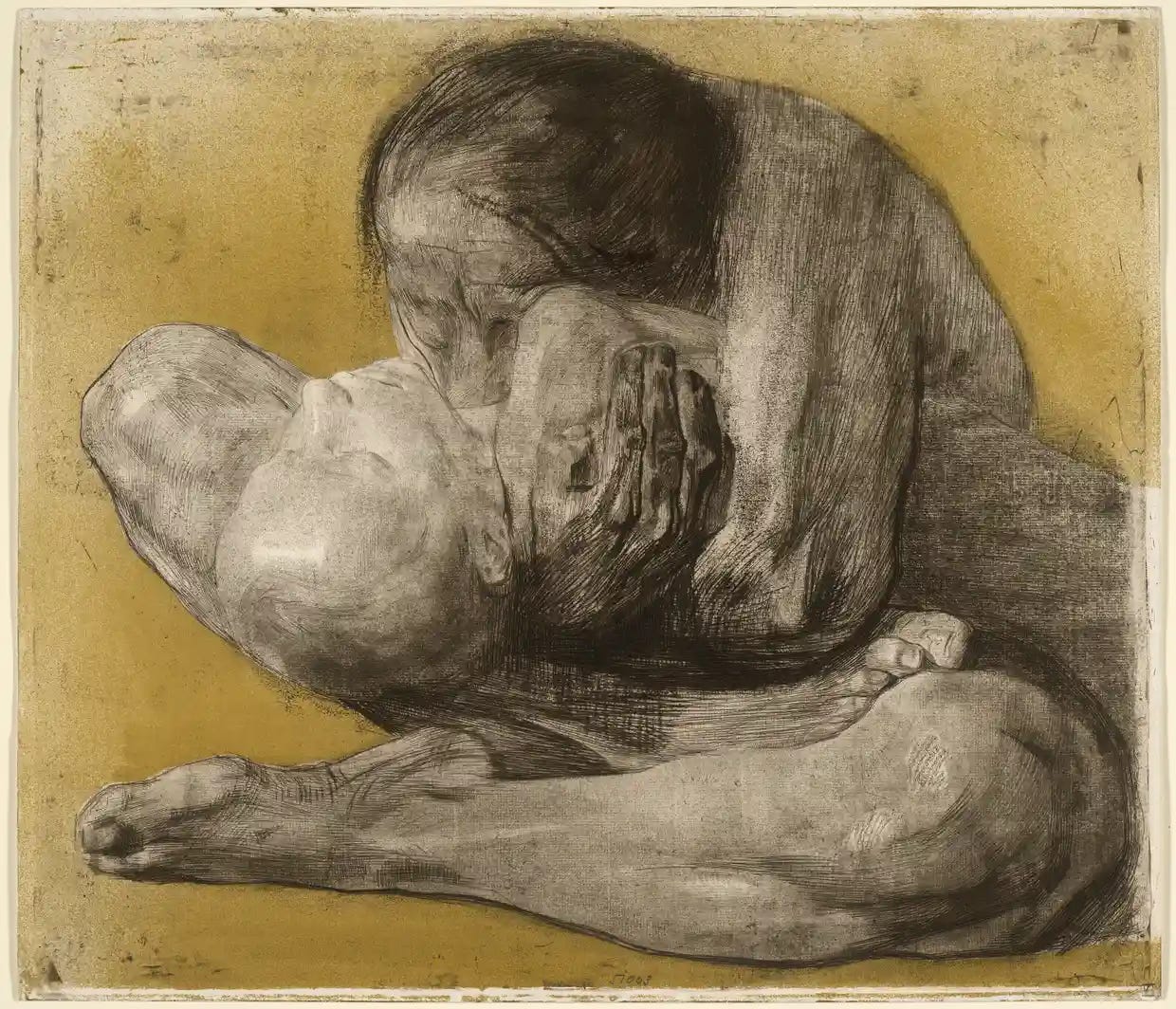

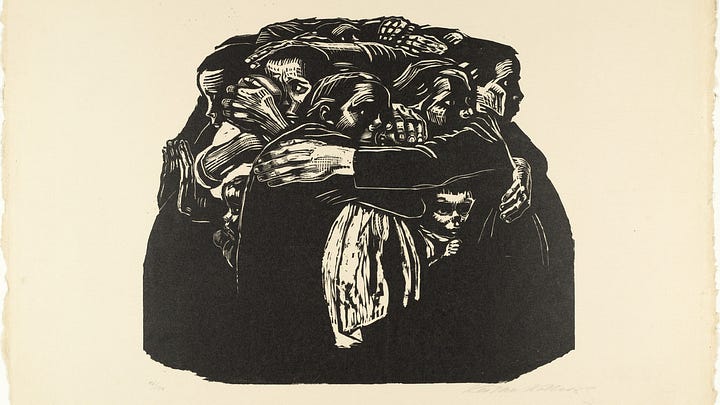

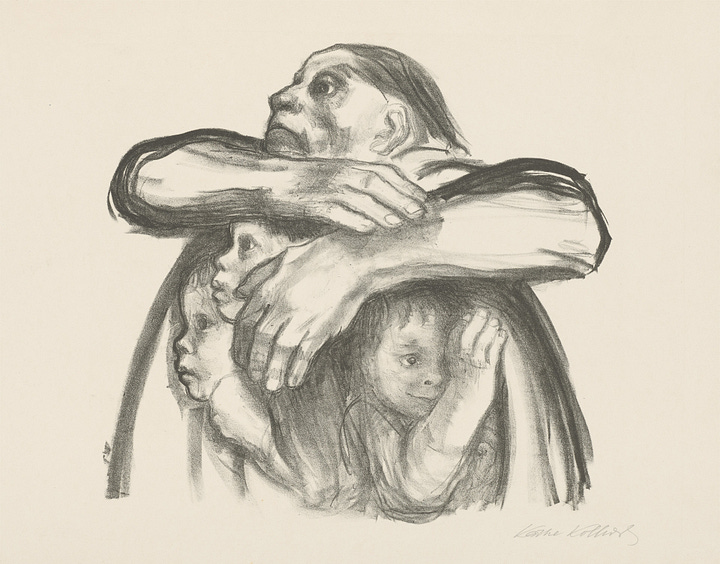

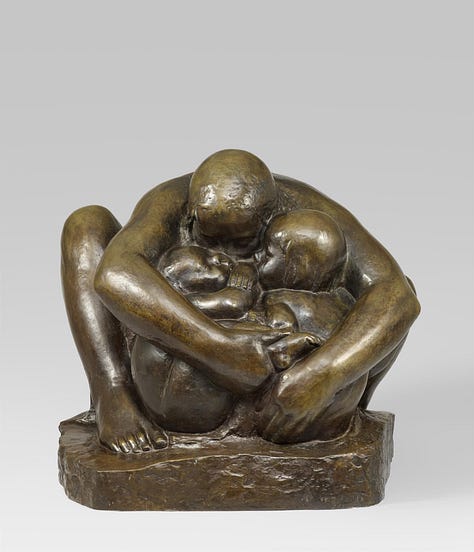

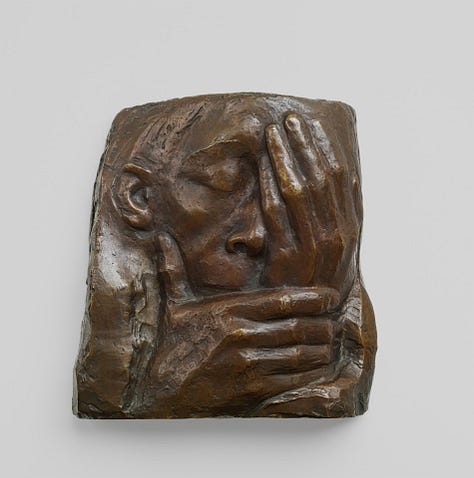

Käthe Kollwitz and Grief

Käthe Kollwitz’s etchings and sculptures embody the weight of being a woman. Her women are usually bowed by grief or the pains of motherhood coupled with the overarching trauma of living through World War Two.

Her women are solid, stoic, and full of gravitas—whilst being crushed by life.

Artemesia Gentileschi and Female Solidarity

Artemisia Gentileschi re-visualised the relationship between Judith and her maid as brute force accomplices in Holferenes’s beheading—instead of the traditional depiction of the maid as a passive witness. In doing so, Gentileschi alters the dynamic of the painting to be not just about a single woman’s revenge but about female partnership and perhaps a more general comment on the injustices women are subject to.

Mary Cassatt’s Home bodies

Mary Cassatt’s domestic scenes of women and children are a tangle of awkward limbs and a minutely observed study of how bodies adjust to accommodate each other. She captures the very essence of what it’s like to be a woman holding the child they’re raising. (Also, I know men care for children nowadays, I’m just not sure they did much in the late 19th century—and they certainly didn’t deem it worthy enough to paint).

Women painted by women often convey the hinted realities of living in a woman’s body, which is anything from tiring to fraught in a patriarchal society. Even on the lighter side, the depictions of motherhood (in the vein of Cassatt, not Kollwitz) are often touchingly intimate, but they aren’t twee family scenes. They communicate something about having borne or cared for a child in a mundane way. Above all, these artworks often capture the ineffable nature of female kinship.

Speaking in very broad brushstrokes, whereas men’s paintings of women often explicitly, or through how they are interpreted, speak to the role of a man in a woman’s life. Women’s paintings of women pull focus to what it means to physically, bodily, and socially be a woman—and how women relate to and understand each other.